Scientific Training

Executive Summary

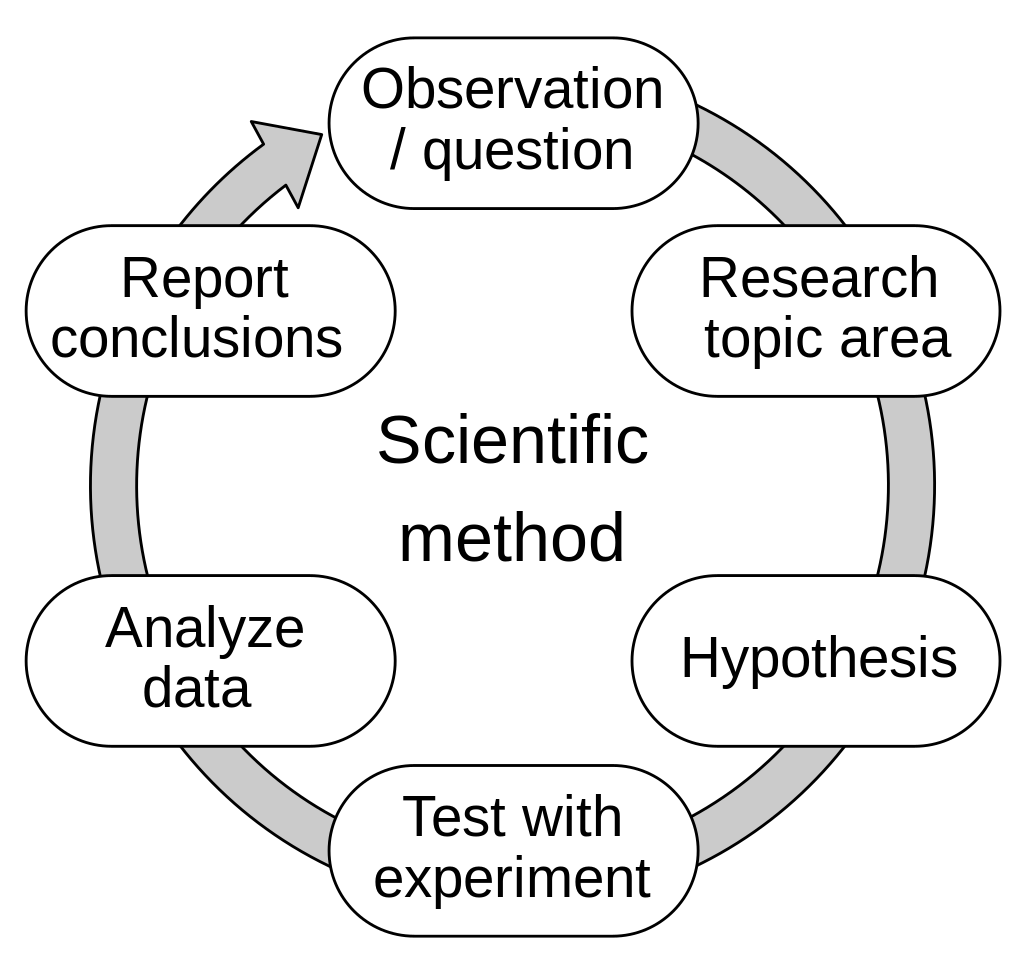

Scientific Training is a method of dog training that follows these steps:

1. Observe

- Identify the problem or challenge.

2. Research

- Are there any evidence-based methods which can be applied?

3. Hypothesize

- Build a hypothesis or chief question.

4. Experiment

- Design and implement an experiment to test your hypothesis.

5. Analyze

- Review the results of the experiment.

6. Conclude

- Make a decision what to do next.

Editorial note: at the time of publication (December 20th, 2023), only a small minority of pet businesses implement evidence-based methodologies . The industry remains fragmented (and inadequate) in it’s approach, and solutions are highly variable among pet professionals therefore.

Example Case: Joel

Imagine that you are working with a client named Joel and his dog, Pilot.

Joel reached out to you because he heard that you might be able to help him with Pilot’s noise reactivity: he gets frightened when he hears loud noises, fireworks, or heavy rain outside.

You, a prolific Scientific Trainer, recommend that he take the three assessments on Dog Food Academy, and perhaps capture some video of Pilot when he can anticipate loud noises will be happening outside.

Joel agrees, and you begin your journey.

Observations

Joel has done an excellent job filling out the assessments, and you are able to identify the key items surrounding this behavior:

1. Stimuli

- Car horns

- The delivery driver’s vehicle

- Fireworks

- Kitchen noises (blenders, dropped pans)

- Thunder

- Rain

2. Sensory Inputs

- Audio or auricular (e.g. horns, vehicle sounds)

- Visual (i.e. flashes of light from fireworks or lightning)

- Fear of harm or injury

- Fear of the unknown

- Stress and anxiety

- Aversion of open spaces (i.e. seeks shelter when presented with the stimuli)

- Suppression of play and social behaviors

- Shakes or trembles

- Reduced appetite and seeking behaviors

- Self-harm (excessive self-grooming)

- Pilot lives in a state where loud noises, which are seemingly random, are a source of anxiety.

- He does not understand that loud noises will not harm him.

- He remains nervous for subsequent days, particularly when fireworks are present.

Research

You’ve read the material listed in Dog Food Academy’s Recommended Reading section, and you have compiled a small list of evidence based information:

- Fear based behaviors are a result of activation of the amygdala (a region of the brain)

- Anxiety is when the amygdala has been sensitized, and is easily stimulated

- The amygdala is desensitized through a process called normalization

- Normalization is catalyzed with proper sleep

Hypothesis

While you understand how and why fear is built, and how to tackle it, you are still operating under a basic assumption that your observations are correct, and that you have approached this with the appropriate tools.

This is your working hypothesis:

- Pilot’s behavior is due to fear of the stimuli

There’s a good chance that it is correct, but you’ve been surprised in the past. Often owners will coddle their pets, and reinforce unwanted behaviors.

For example, if the owner observes that their dog is startled, they will pet and coo the animal – which may just reinforce the behavior itself!

You are careful not to be too sure in your working hypothesis, because a competing hypothesis is equally as likely:

- Pilot’s response is maintained through constant reinforcement of the behavior (also called “conditioning”)

Experimentation

Joel is excited; you’ve called him with a plan to tackle Pilot’s noise reactivity. Knowing that Graded Exposure Therapy relies on a stair-stepped approach, you outline this plan:

- Obtain a household speaker

- On low volume, play sounds of rain (the sounds can vary as Pilot grows used to them)

- Training nearby helps, such as working on movement commands: heel, recall, fetch

- As the days pass, turn up the volume, slowly.

- On a separate session, practice turning the lights on then off, and give Pilot a treat.

- As he grows used to the sensation, you may pair this with the sound of thunder through the speaker.

You continue to layout your plan, showing Joel how and where to introduce new stimuli, and what to look for if he is introducing new things too fast.

Joel agrees to implement this training over the coming weeks.

Review

You call Joel for a follow-up and are pleased with what you hear:

- Pilot didn’t react to a car horn recently

- His response to outside noises seems to be diminishing

- Joel is sticking to the plan and is happy thus far

Excellent, things seem to be going to plan. You encourage Joel and assure him that he can tackle this behavior if he keeps up the consistency.

After two months, Pilot’s anxiety has been addressed, and he no longer reacts to loud noises – there was even a thunder storm with flashes of light and Pilot did great!

Conclusion

This is excellent, your experiment worked on the first run, congratulations!

You make a note in Joels client record:

- Hypothesis used: fear of stimuli

- Therapy technique: graded exposure

- Result: positive, diminished fear response

You a happy for this outcome, because you know that you have to go back to the drawing board sometimes. A list of possible negative outcomes would be:

- Joel introduced the stimuli too fast, and reinforced Pilot’s fear response.

- Joel was inconsistent in his training, and Pilot didn’t make progress.

- Pilot’s reactivity was not just fear-based, but reinforced with coddling.

Any of these scenarios could send you back to the drawing board, and you are thankful that they didn’t!

Scientific Training

Great job with Joel, you are a rockstar!

As you might have noticed, this is the process that is used in the research field: the scientific method. While there is already a wealth of knowledge online, it is helpful to see it in action and how it might play out in the pet industry.

The term “Scientific Training” really just means “evidence-based”. A Scientific Trainer will be well-read and educated in various training techniques and how to implement them.

Because there is no certification program for Scientific Training, it is important that your trainer provide reference material upon request (a good source of information might be this website).

A competent trainer will always be transparent and communicative.

How to?

Since this training style can adopt any technique (as long as it has been studied), there is no “one way” to learn this method.

That being said, we highly recommend starting with a cynopraxic approach, as outlined in Steven Lindsay’s textbook series called Applied Dog Behavior and Training, which can be found in our recommended reading section.

The textbook, essentially, is a compilation of research that Lindsay has adapted into training techniques. Which is at the heart of Scientific Training!

In addition, adhering to the scientific method (like with Joel) ensures that you have a consistent framework.